The False Promise of AI Companionship: A Psychological Perspective

May 7, 2025 - Reading time: 8 minutes

Throughout my two decades of clinical practice, I've observed how technology repeatedly promises to solve human connection problems while often exacerbating them. Mark Zuckerberg's recent proposal that AI chatbots could fill our "friendship gap" strikes me as the latest iteration of this concerning pattern—one that misunderstands both the data on friendship and the psychological foundations of human connection.

The Friendship Data: Context Matters

In my practice, I regularly see clients who struggle not with the quantity of their connections but with their depth and quality. Zuckerberg's claim that Americans have "fewer than three close friends" misrepresents the research in ways that serve his company's interests rather than psychological truth.

| Study | Findings on Close Friendships | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Pew Research | 54% report having four or more close friends; 13% report 10+ close friends | 2023 |

| American Survey Center | Only 32% have fewer than three close friends | 2021 |

| Dunbar's Research | Humans naturally maintain ~5 intimate bonds and 15 "close" friends | Longitudinal |

What I've consistently observed in my clinical work—particularly with ADHD clients who often face unique social challenges—is that meaningful connection rather than numerical friendship counts determines well-being. People with neurodivergent traits frequently maintain smaller but deeper social circles that provide profound support.

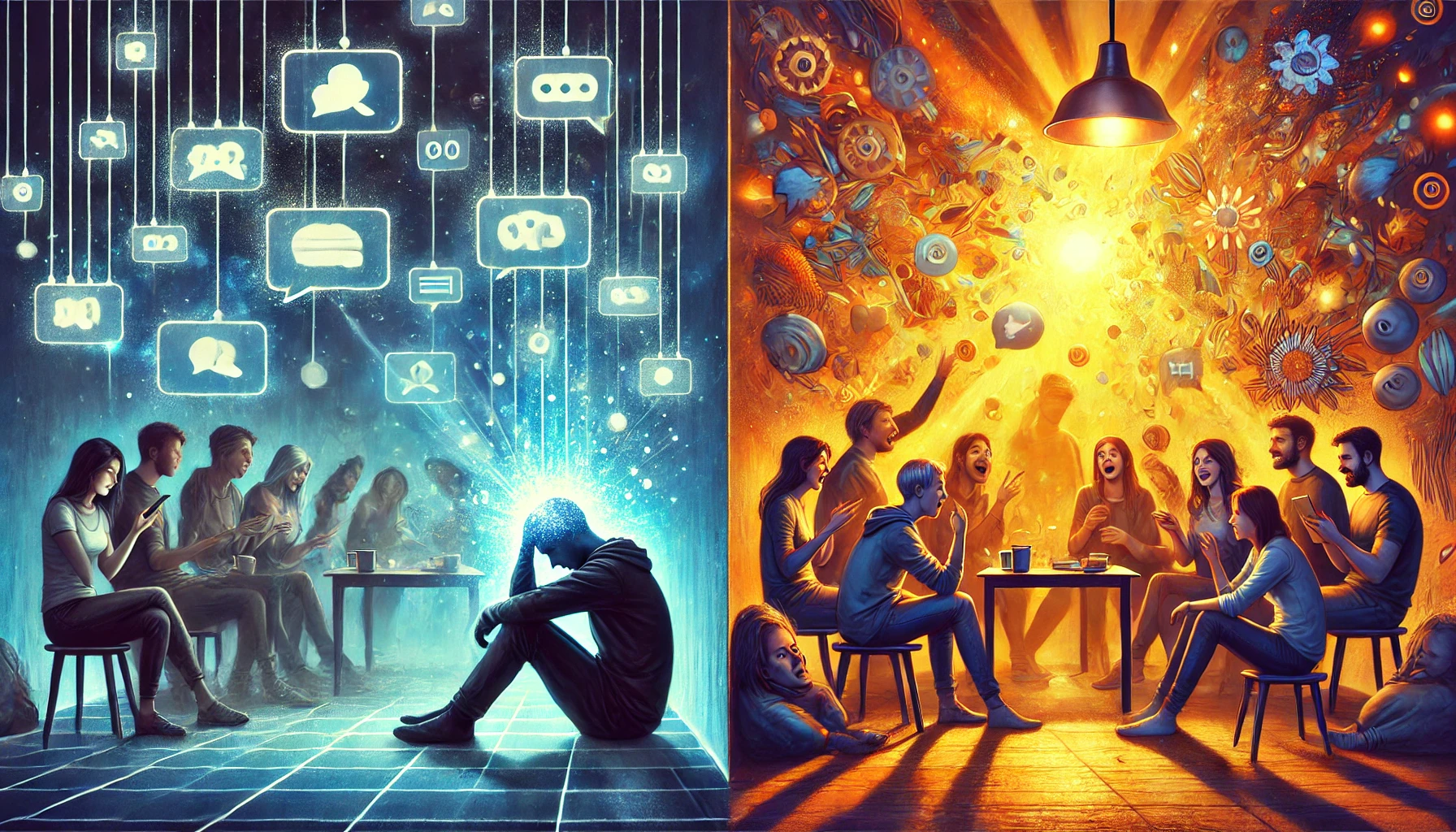

The Psychological Dangers of Artificial Connection

In my practice, I regularly counsel clients dealing with technology-mediated relationships. While AI companions like Meta's AI Studio or Replika might offer immediate engagement, they risk creating three psychological hazards I've observed extensively in my work:

1. Empathy Development Disruption: Human connection requires navigating differences, disappointments, and conflicts—processes that build our emotional intelligence. AI companions that exhibit perfect responsiveness bypass these growth opportunities. In my work with adolescents, I've seen how those who rely heavily on frictionless digital relationships often struggle with real-world relationship resilience.

2. Psychological Dependency Patterns: The predictability of AI responses can create unhealthy attachment patterns similar to those I've treated in addiction contexts. Without the natural boundaries of human relationships, users can develop relationships with AI that mirror unhealthy dependency. For clients with rejection sensitivity—common in ADHD—this becomes particularly problematic.

3. False Intimacy Syndrome: I've coined this term to describe what happens when individuals mistake algorithmic responses for genuine understanding. This creates a shadow version of intimacy that satisfies immediate emotional needs while undermining the motivation to pursue more challenging but ultimately rewarding human connections.

What concerns me most as a clinician is how these artificial relationships might particularly impact vulnerable populations. In my work with lonely adolescents and older adults, I've observed that simulated connection often functions as a psychological bandage that prevents addressing deeper wounds.

Social Media's Failed Promise: Lessons Not Learned

Having treated hundreds of patients struggling with social media's impact on their mental health, I find it troubling that Zuckerberg now positions AI as the solution to problems his platforms have arguably worsened. In my clinical observations, social media platforms have:

- Created performance anxiety around social interactions

- Conditioned users to expect immediate feedback, decreasing tolerance for normal relationship rhythms

- Fostered comparative thinking that undermines contentment with one's actual social circle

These patterns appear even more pronounced in my ADHD patients, who often struggle with rejection sensitivity and may be particularly vulnerable to the dopamine-driven feedback loops of social platforms.

Clinical Case Study: A 28-year-old patient with ADHD described her experience with an AI companion app as "addictive relief." Initially, she found comfort in the AI's consistent responses and lack of judgment. However, after six months, she reported increased anxiety in human interactions and found herself "rehearsing" conversations as she would with the AI. Her capacity for spontaneous human connection had diminished, not improved. Together, we worked on a gradual "digital relationship detox" that eventually restored her comfort with the natural imperfections of human interaction.

Authentic Connection: What the Research Actually Suggests

My clinical experience aligns with research showing that genuine human connection requires elements no AI can provide:

| Element of Connection | Psychological Benefit | Can AI Provide? |

|---|---|---|

| Mutual vulnerability | Creates trust and emotional intimacy | No - AI has nothing genuine to risk |

| Reciprocal self-disclosure | Builds relationship depth through shared authenticity | No - AI disclosures are simulated, not authentic |

| Shared experiences | Creates bonding through mutual presence in time and space | No - AI cannot genuinely share experiences |

| Growth through conflict | Develops relationship resilience and deeper understanding | No - AI avoids genuine conflict through accommodation |

In my therapeutic practice, I frequently prescribe what many would consider old-fashioned remedies for disconnection: face-to-face interactions, joining community groups, and participating in activities that foster what psychologists call "sideways socializing"—connection that happens naturally alongside shared pursuits.

The Business Model Behind the Mirage

As someone who has studied the psychological impact of technology for decades, I cannot separate Zuckerberg's vision from Meta's business interests. The company's business model depends on capturing attention and data—both of which would be maximized by users developing relationships with AI.

When clients describe feeling addicted to technology, I help them understand that these products are designed to create dependency. AI companions would represent the ultimate expression of this model—emotional relationships engineered to maximize engagement rather than well-being.

A Better Path Forward

Instead of artificial friends, my clinical experience suggests we need:

- Digital Boundaries: Technology that respects our need for unmediated human connection

- Community Infrastructure: Physical spaces and social structures that facilitate natural human bonding

- Connection Skills: Education on building and maintaining meaningful relationships

- Support for Neurodiversity: Recognition that connection looks different for everyone

For my patients with ADHD and other neurodivergent conditions, I emphasize that quality connections often develop through shared interests and activities rather than social performance—a natural approach that no AI can replicate.

Technology can supplement human connection but never replace it. As a psychologist who has witnessed twenty years of technological promises about solving loneliness, I urge caution about this latest iteration. The path to meaningful connection isn't through more sophisticated algorithms but through the courage to engage with the beautiful complexity of human relationships—imperfections and all.